No history, no future.

No history, no future.

*an edited version of this essay will appear as the introduction the forthcoming book “Images of America, Milwaukee Jazz” by Joey Grihalva on Arcadia Publishing Co. (preorder the book here: mkejazzbook.com)

Many have proclaimed the “death of jazz” since the musical art form began over a century ago. In response to such proclamations, Milwaukee Jazz guitarist Manty Ellis says, “You can’t kill a cultural art form. They try to kill the music, but when they stomp it out here, it grows up over there. They kill it over there, it comes up over here.” It is a disgraceful if unsurprising fact that the music born out of the oppression and suffering of Black Americans has not been fully embraced in the country in which it was created.

Several years ago I began documenting the history of the under-appreciated, if not completely unrecognized jazz scene in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The impetus for the project was that I had found very little online or print evidence of Milwaukee’s rich and storied jazz history, and little mention of particular notable individuals. Important Milwaukee musicians such as Berkeley Fudge, Hattush Alexander, Manty Ellis, Penny Goodwin, Tony King, Will Green, Jessie Hauck, Bob Hobbs, and Dick Smith, to name just a few, influenced and inspired generations of Milwaukee jazz artists. Speaking of guitarist Manty Ellis, alto saxophone legend Frank Morgan said, “I can’t say enough. There are some bright stars on the horizon who owe their life to him. He’s a legend in his own time. I love him and there should be a monument erected to him in Milwaukee.”

Not unlike other midwest cities of comparable size and stature, (Detroit, Chicago, Cleveland, for example) Milwaukee has struggled with many of the same societal problems: deep segregation, the decline of the blue collar working class, unemployment, disadvantaged and underfunded education systems, institutionalized racism, and poverty among many other issues. Milwaukee, a microcosm of America at large, has all but ignored its most important Black cultural entities. This ignorance is evidenced by the complete decimation of “Bronzeville”, Milwaukee’s historic Black district, for the construction of the interstate in the late 1950s and 60s and done in the name of “urban renewal”. Thousands of private homes, black-owned businesses, restaurants, nightclubs, and community organizations were destroyed, leaving nothing but faded memories of more prosperous times. In 1967, the Milwaukee City Council voted against a fair housing edict that would have protected blacks from racial discrimination. This act of inequality purveyed by the City Administrators ignited months of violent protests. A quick Google search of Detroit’s “Paradise Valley” reveals an eerily similar story of freeway construction, planned “urban renewal”, displaced families, destroyed businesses and cultural centers, leading to segregation and ongoing social inequality. Milwaukee’s inherent segregation meant its schools did not integrate following the landmark 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision. A 1960 study completed by the NAACP found that schools in the city of Milwaukee proper were 90 percent black, despite the important national decision and the growing movement to desegregate.

Often times the evidence of this history is right in front of our faces, hiding in plain sight. Buildings you may have driven past hundreds of times and paid no attention to contain the echoes of icons of American music and entertainment. The Ron-De-Voo Ballroom, which hosted the legendary Billie Holiday for four consecutive nights in August of 1953, is just one example. The Ron-De-Voo Ballroom (1118-26 North Ave) still stands to this day, however it is hidden by decades of decay and neglect. The Riverside Theater (116 West Wisconsin Ave), to which thousands of young indie-rock music fans now flock, once hosted the Cab Calloway Orchestra in February of 1940, and Duke Ellington in July of 1939. The Bombay Bicycle Club in the Marc Plaza Hotel (509 Wisconsin Avenue, currently the Hilton Milwaukee City Center) was the site of jazz legend Buddy Montgomery’s house trio six nights a week for ten years from 1970-1980, after he relocated to Milwaukee from his native Indianapolis. The historic and now iconic Pfister Hotel contained the Crown Room (424 East Wisconsin Avenue, currently Club Blu) which opened in 1966 and regularly featured the likes of such jazz luminaries as Sarah Vaughan, Lionel Hampton, Pete Candoli, Carmen McRae, and Billy Eckstine, to name a few. One could also hear piano and organ master Melvin Rhyne (of Wes Montgomery fame) six nights a week in the mid-1970s at the Cafe Olé, in the Pfister’s lobby bar. The Pfister Hotel, to this day, is a hub of activity in Milwaukee’s vibrant nightlife scene; providing an outlet for new generations of Milwaukee musicians. In some cases, all that is left is an invisible footprint. Clubs such as The Main Event, (3418 N Doctor M.L.K. Jr Drive, active from 1974-early 2000s) now demolished, were an essential part of Milwaukee’s music scene.

The original Jazz Gallery (926 East Center Street, owned and operated by jazz-warrior Chuck LaPaglia) ran international-caliber jazz programming from 1978-1984 in Milwaukee’s Riverwest neighborhood. The number of jazz luminaries that graced the Jazz Gallery’s stage during its six years of operation are too numerous to list here. After the venue’s demise, the space housed number of different ventures including a rock club and a corner bar. The bar was ultimately closed and the building was divided into residential space. Currently operated by The Riverwest Artist Association (RAA), and thanks to a partnership between RAA and the Milwaukee Jazz Vision, the space has been revitalized into a community art/music venue once again. The Jazz Gallery Center for the Arts has embraced and honored its history and is now thriving.

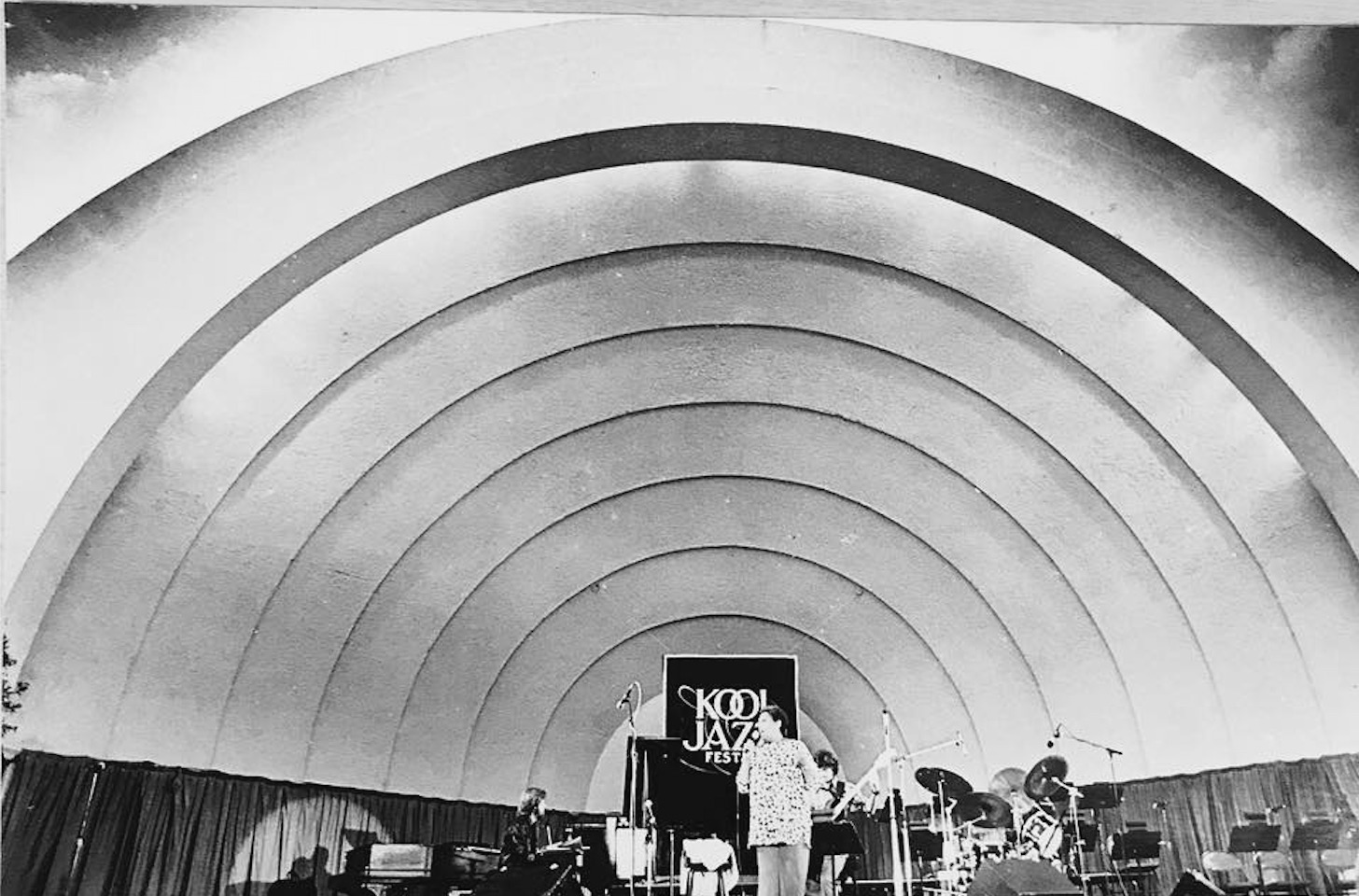

Milwaukee’s Summerfest once boasted a staggering line up of international jazz super stars amongst its annual festival performers. Sadly, the flagship “Jazz Oasis” stage went away decades ago. However, recently due to MJV’s partnership with Milwaukee World Festival Inc. Summerfest now has a renewed interest in presenting and supporting local jazz has been reflected in the (now 5th annual) Visions On the Lake Festival and their Summerfest Jazz Day, both making a nod to its jazz past and inspiring future generations of Wisconsin jazz musicians.

Historic venues such as The Jazz Estate and Caroline’s Jazz Club have, against all odds, remained shining lights of cultural strength through the decades. The century-plus old Wisconsin Conservatory of Music continues to follow in the footsteps of jazz program founders Tony King and Manty Ellis by providing Milwaukee’s young musicians a world-class education – recently winning DownBeat awards, placing in national competitions and hosting international jazz stars for clinics, festivals and concerts.

The driving force behind the Milwaukee Jazz Vision and the book you are now holding has been a desire to shed some light on the contributions of these unsung regional masters, under past and present. My hope is that this book will not be just a nostalgic look back at our rich past, but an inspiring intimation of what is possible in the future.